This is Part 2 of my short series: From Draft to Published — a minimalist guide to writing, formatting, and publishing your book without overwhelm. Start with Part 1 here.

If you write (for yourself or as part of your job or both), you probably have a favorite writing app. Maybe it’s Word, or Scrivener, or Vellum, or even Google Docs. Or maybe other cloud-based tools like Atticus or Reedsy (or whatever the latest writing tool is).

Me? After years of trying different tools and formats, paying for expensive applications and upgrades (or subscriptions), and trying to learn bloated software that tries to be everything—word processor, planner, typesetter, even marketer—I stopped looking for the perfect writing app—and just started writing in plain text.

Why? There are many reasons why I’ve written plain text files for years, but those reasons boil down to three simple ideas: freedom, simplicity, and control. Plain text files are:

Portable:

Plain text files can be opened, read, edited and saved on any platform (Mac, Linux, Windows) and by any writing application. It’s been this way since there were computers, and I expect it will be into the future. Plain text is the foundation of every other format. You can work with plain text on any device with a text editor. You don’t need a Mac, or a Windows PC, or any special platform.Accessible without the ‘cloud’:

Unlike ‘cloud’ apps like Atticus (which requires an Internet connection even if you use it on the desktop), Office 365, Google Docs, and many others, you can just write and edit text files offline, in any text editor you have available.Convertible:

Plain text can be converted to any other format you need—PDF, EPUB, DOCX (Word), FDX (Final Draft), even JSON. It’s the foundational source material for most every other format out there.Free (as in free and freedom):

You don’t need to buy an application, or a subscription, or buy another software update to write and use plain text. You can use any writing application you want, because plain text has been readable by most any writing application for decades, and will be in the future. It’s not dependent on specific applications, proprietary formats, or operating systems. And it’s 100% free and always will be.

It sounds too good to be true, doesn’t it?

This post is about the simple, text-based workflow I now use to write, organize, and format my books and other writing—from first draft to publish-ready files. It’s not flashy, but it’s clean, reliable, and future-proof.

If you’ve ever felt distracted by your tools, or worried about your work being trapped in some proprietary format you can’t open later, this might be the path you didn’t know you were looking for.

Are There Disadvantages?

Yes. Depending on what you write, writing in plain text may require a little more ‘hands on’ work, especially if you’re writing books or other documents you want to convert so you can publish and share.

But you can start by simply starting with writing plain text; these hands-on skills and set up are quickly learnable, and using plain text opens up a whole world of freedom, control, and simplicity that dependency on other tools and technologies can’t match.

My Writing Environment & Workflow

I write all of my books, notes, and most everything else using plain text files with a lightweight syntax called Markdown. “Wait”, you’re probably thinking. “Didn’t you say ‘plain text’?” Yes I did—but Markdown is still plain text. Let me explain:

Why Markdown?

Markdown is just characters in plain text that denote formatting (headings, lists, quotes, etc.). It has all the advantages of plain, unadorned text that I mentioned earlier.

For example, writing a chapter in Markdown might look like this:

# Chapter One

This is the first paragraph of my book.

## A Subheading

Here’s some more text.

Want italics? *Like this*.

Bold? **Like this**.

- You can add bullet points

- Or numbered lists

- Even images or linksYou’re still writing plain text—just with a few extra characters that can be used later if you convert the plain text to something else (or if not, for visual cues about the organization of your text file). And that’s the fundamental reason I use it: it simplifies reading text files now, and the process of converting them (to a book, etc.) later.

The Tools I Use

Here’s my actual setup:

1. Editor: Zettlr

Zettlr is a clean, distraction-free Markdown (plain text) editor. It’s a desktop app, and comes with a lot of nice, user-friendly features. And it’s available on Mac, Linux, and Windows. Oh—and it’s completely free and open source.

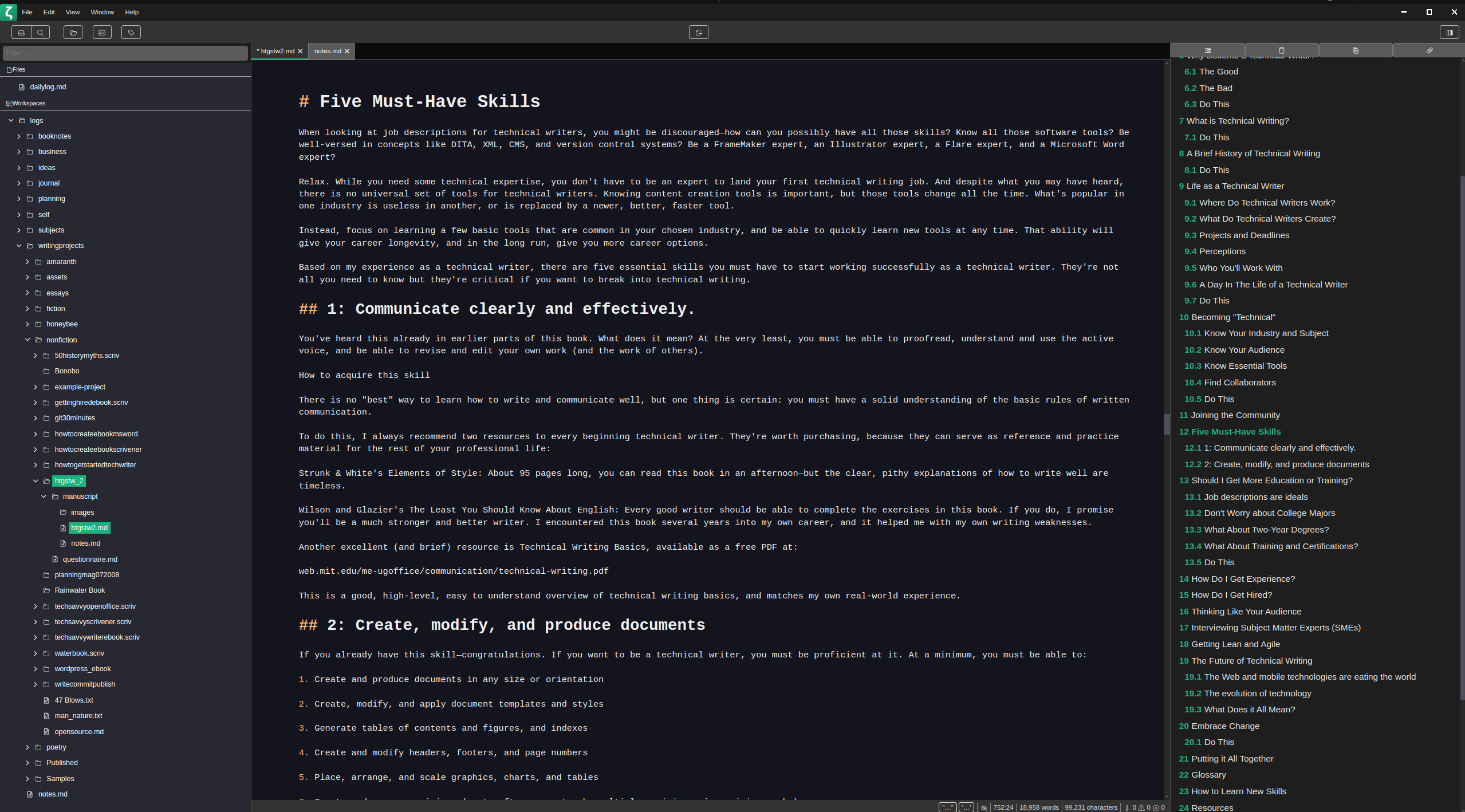

I love Zettlr. For example, here’s a recent screenshot of me writing a book in plain text (with Markdown) in Zettlr:

A nice Zettlr feature: it even shows a nice table of contents of my Markdown file, and it’s clickable—I can quickly navigate around in my file by clicking the content links.

2. Folder structure

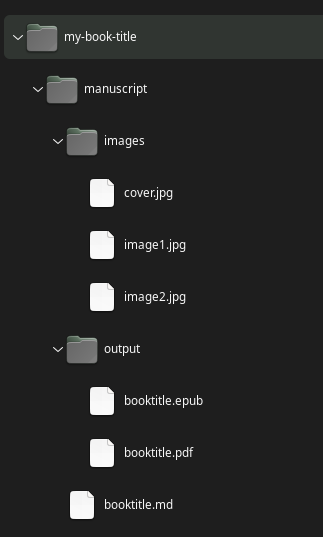

For book projects, I keep projects files in a folder like this:

It’s fairly simple: every book gets its own directory (folder), and inside that is the manuscript and any supporting files—cover images, interior images, the output files (EPUB for Amazon, for example). In the image above, booktitle.md is the entire book.

NOTE: the ‘.md’ file extension you see here is just a common file abbreviation for a markdown file; but it’s really just a text file, and any text editor will open it.

I used to keep each chapter is its own file (and you can too), but I’ve found keeping the entire book in one file makes it easier for me to navigate in Zettlr.

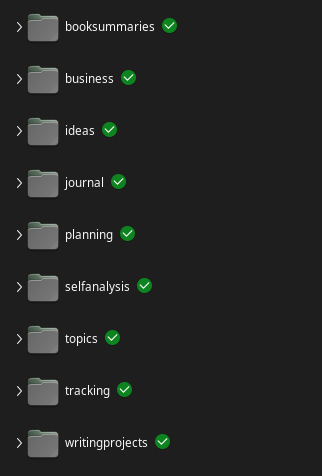

For all my other plain text files (journals, letters, etc.? I generally group them by topic, like this:

As you might guess, that earlier book example is inside the writingprojects folder. But believe it or not, almost all text files I write are contained in this simple set of folders.

3. Version control (optional): Git

If you write books or do other long-form writing, you probably have a system for keeping track of versions. I know for many this is cleverly named files like ‘draft1’, ‘draft2.doc’, ‘draft-05-10-2024.tdoc, ‘draft-06-12-2024-FINALFINAL.doc’, and so forth. Some writing apps help with this, but the way I do it is much simpler: I either don’t track versions, or I use Git.

Git is a version control tool, most commonly used by tech-savvy folks to track changes in software projects—but it can be used for text, too (software is often written in plain text files). You might have heard of Github, which is just a large, online storage system for Git project repositories. If you’re comfortable with Git, it’s a great way to back up your work and track changes.

My advice? If you’re comfortable with tools like this, it’s a game-changer. If not, consider letting go of the need to save off dozens of versions of your text files, and just periodically back everything up. Doing this or using Git—whatever you do, don’t let it slow you down.

4. Conversion tool: Pandoc

Pandoc is a kind of ‘universal translator’ tool that takes Markdown files and turns them into beautiful PDFs, EPUBs—or most any other format you want (and vice versa).

It’s powerful—but not complicated if you start with a template or a one-line command. More on that in the next post; for now, just know that it automates creating the publish-ready files that distributors like Amazon need.

Why This Setup Works

This approach helps me focus on writing—and lets me format and export only when I’m ready, with minimal friction.

Next up

That’s the overview of how I do it. In the next post, I’ll explain how I take these plain text files and turn them into publish-ready formats—PDF, EPUB, and more—with just a few steps.

You don’t need to be a developer to do this. You just need the right process—and I’ll walk you through it.

Questions? Curious about something I mentioned here? Please reply or leave a comment—I’d love to know what part of this feels interesting (or intimidating), and I’ll try and answer any questions you have.